I recently shared a post on the importance of plant diversity for your health, and today I want to dive deeper into one of the most underrated aspects of gut health: dietary fibre.

If you’re struggling with digestive issues, weight management, blood sugar imbalances, or thyroid dysfunction, the answer might be simpler than you think. Most New Zealanders are consuming just 20g of fibre daily, falling 5g short of even the minimum recommendation.

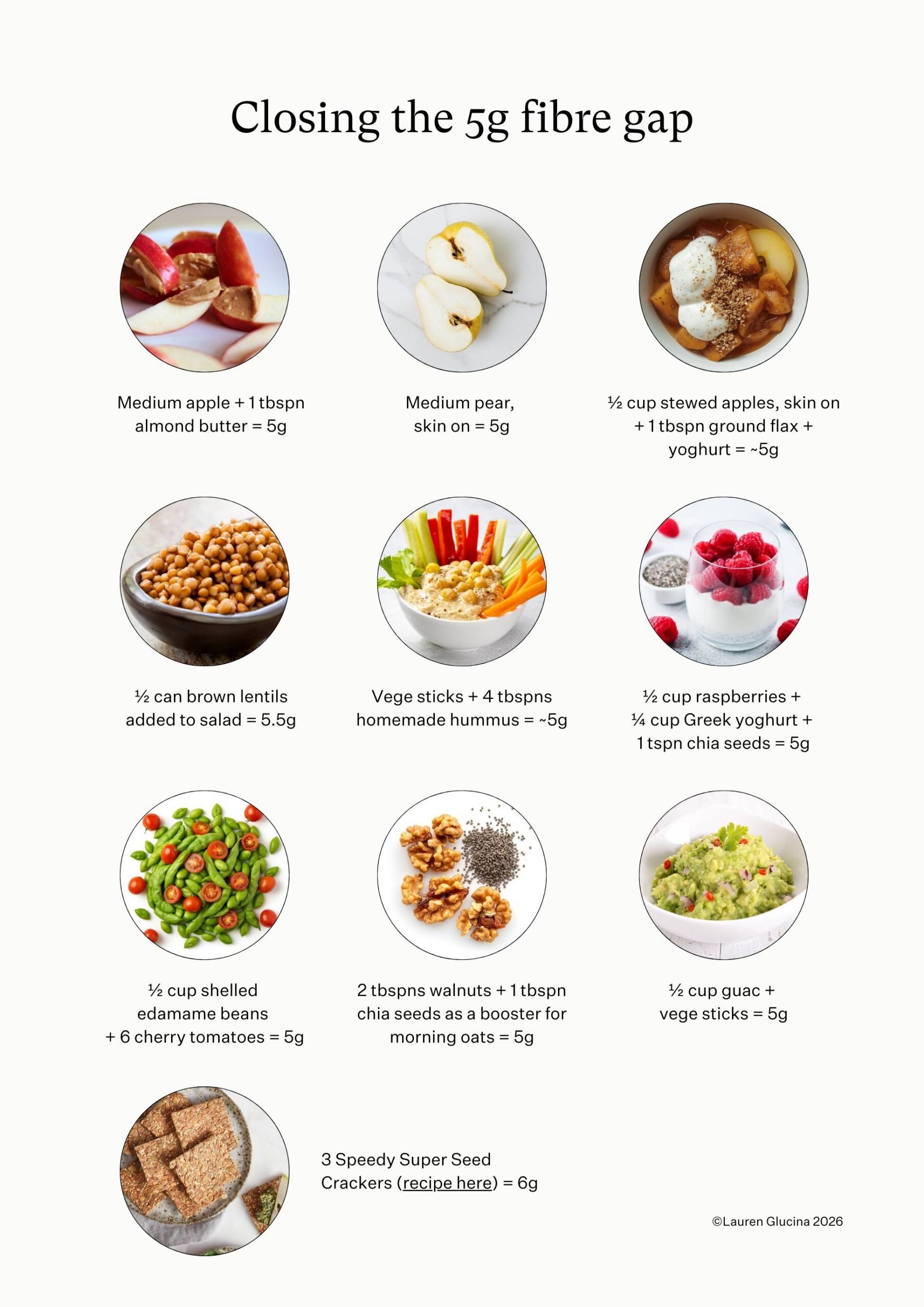

Today, I’m showing you how to close that 5g fibre gap and why it matters far beyond your digestion.

Dietary fibre is the part of plant foods (fruits and vegetables, whole grains and legumes, nuts and seeds) that your body can’t digest and your gut microbes depend on to thrive.

We need both variety and quantity, as different microbes have different taste preferences, and we want to keep them all well-fed. So in a sense, we’re not just eating for one – but trillions!

If the diet is lacking in fibre, then our gut microbes will naturally seek food elsewhere. They may start to break down proteins and degrade amino acids, which can lead to potentially toxic by-products.

Unfortunately, many will start to degrade the protective mucin (mucus) layer of the gut lining instead, which can expose the epithelium (cells of the gut wall) to pathogens and toxins, resulting in increased inflammation and a weakened gut barrier – to the extent it can even become more permeable than it should.

For my thyroid readers, a weakened, permeable gut barrier is a known driver to autoimmunity and can initiate an autoimmune attack against the thyroid gland. This is just one reason why gut health is so important to consider when working with conditions like Hashimoto’s and Graves’ disease.

🥝🥑 Fibre’s role is so important that nutrition experts from Otago University are calling for it to be officially recognised internationally as an essential nutrient, which would make it the first ‘new’ essential nutrient in over 50 years (Reynolds et al., 2026). 🥝🥑

Fibre, fibre, fibre!

Dietary fibre can be classified as soluble, insoluble, resistant starch and prebiotic.

Soluble fibre dissolves in water and is readily fermented by gut bacteria, supporting their growth and the production of beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids. These nourish colon cells and trigger a cascade of health benefits throughout the body.

Soluble fibre also helps normalise bowel movements, softening hard stool in constipation and firming loose stool in diarrhoea.

Examples include oats, nuts and seeds (like psyllium husk, flax, and chia), lentils, and the skins of many fruits and vegetables (such as apples and citrus).

Insoluble fibre doesn’t dissolve in water and resists bacterial fermentation. Instead, it adds bulk to the stool and promotes regular bowel movements, helping prevent constipation.

Examples include whole grains, wheat bran, nuts, and vegetables.

🥭 🫑 Most fruits and vegetables contain a mix of both soluble and insoluble fibre.🥭🫑

Resistant starch and prebiotic fibres function similarly to soluble fibres, in that they pass through to the large intestines where they are readily fermented by bacteria to exert health benefits. Resistant starch in particular will help fuel butyrate producing bacteria and strengthen the gut barrier.

Examples of resistant starch include cooked and cooled potatoes, legumes and greener bananas.

Examples of prebiotic fibres include garlic, onions, leeks, chicory root, artichokes and asparagus.

Benefits: The gut and beyond

Across a wide range of studies, increasing fibre intake is consistently linked to improvements in body weight, cholesterol, blood sugar control, and blood pressure.

It’s also essential for safely eliminating used oestrogen from the body, preventing it from being reabsorbed through the gut.

For my thyroid clients, this is particularly important: excess oestrogen can contribute to hypothyroidism by elevating thyroid binding globulin (TBG), which reduces the amount of free thyroid hormone available and causes TSH to rise.

The long-term benefits are equally compelling. Research following people for decades shows that those who eat more fibre have significantly lower risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and colorectal cancer, and are more likely to live longer, healthier lives.

How much do we need?

Hunter-gatherer societies consumed 100g or more of fibre per day (Eaton, 2006). Today, the average New Zealander consumes just 20g daily, falling short of the recommended WHO intake of at least 25g.

Emerging microbiome research suggests we may need even more – closer to 50g (!) – based on ancestral diets and intervention studies showing improved gut microbiome diversity at these higher levels.

However, when increasing fibre intake, it’s crucial to go slowly and ensure you’re adequately hydrated, to avoid symptoms like bloating, abdominal discomfort and constipation.

Note: Those with IBS or gut dysbiosis may need to increase fibre more gradually under practitioner guidance.

Close the 5g fibre gap

Add a fibre-rich snack or booster to reach 25g as a first step. Once your gut adapts, you can gradually increase fibre intake further over time.

Fibre boosters

Here are some great examples of gut-healthy options to include:

- Medium apple + 1 tablespoon almond butter (5g)

- 3 Speedy Super Seed Crackers – recipe here on my food blog Ascension Kitchen (6g)

- Medium pear, skin on (5g)

- ½ cup stewed apples (skin on) + 1 tablespoon ground flax seeds with yoghurt (~5g)

- ½ can brown lentils added to your salad (5.5g)

- Carrot sticks with 4 tablespoons homemade hummus (~5g)

- ½ cup raspberries, ¼ cup Greek yoghurt, 1 teaspoon chia seeds (5g)

- ½ cup shelled edamame + 6 cherry tomatoes (5g)

- 2 tablespoons chopped walnuts and 1 tablespoon chia seeds (5g) – as a booster for morning oats

- ½ cup guac (5g) with vege sticks/crackers

The nervous system catch

Just when you think you’ve nailed gut health… let me just say that no amount of gut support can compensate for a nervous system stuck in fight or flight! So please factor this into your health plan, it matters more than you might think.

Small, consistent practices can make a real difference. Things like getting morning sunlight, breathwork, spending time in nature, tuning into your senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste), slowing down, and taking bitter herbs (especially before meals) all support the vagus nerve, which sits at the heart of the gut-brain connection.

Final thoughts

A wholefood, plant-rich diet provides ample diversity and dietary fibre, nourishing the gut microbiome and protecting the intestinal lining. The benefits reach far beyond the gut itself, so much so that fibre deserves recognition as an essential nutrient

If you feel you could benefit from individualised care, reach out for a clarity call with me or book in for a consult. Let’s do this together,

Lauren.

References:

Reynolds, A., Cummings, J., Tannock, G. & Mann, J. Dietary fibre as an essential nutrient. Nature Food 7, 4–5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-025-01282-0

Eaton, S. The ancestral human diet: what was it and should it be a paradigm for contemporary nutrition? Proc Nutr Soc. 2006 Feb;65(1):1-6. doi: 10.1079/pns2005471. PMID: 16441938.

Feeling burnt out or off your game?

It might be low iron, B12, magnesium, zinc, or vitamin D. Watch Nutrient Foundations for Energy, Mood & Resilience to learn where to start.

X

Comments +